Why Banks Must Invest in Compliance Built for State–Federal Drift

Contents:

- Who Is Driving Enforcement and Why It Now Moves on Two Tracks

- The Six Domains Where Rules Are Shifting

- How Enforcement Is Changing: The New Supervisory Posture

- What Modern Compliance Looks Like

- The Architectural Imperative

Regulatory pressure in the US is widening across multiple layers of supervision, each moving on its own clock. States are tightening rules on fees, disclosures, and interest practices, while federal oversight is expanding to data rights, third-party risk, and operational resilience. The result is divergent regulation. These are changes that land differently across jurisdictions and pull all stakeholders into deeper scrutiny. In this environment, compliance must be viewed from an architectural lens, in addition to a policy one.

This analysis addresses the impact of divergent requirements on institutions and the architectural expectations placed on core platforms and TSPs supporting multi-jurisdictional operations.

To make sense of this shift, we’ll look at it across three axes: who is driving enforcement, what exactly is being regulated, and how enforcement itself is evolving.

Who Is Driving Enforcement and Why It Now Moves on Two Tracks

In 2025, the compliance burden has been created by two enforcement systems accelerating at the same time, but not in the same way.

State Enforcement Is Moving Faster, With Broader Tools and Lower Thresholds

States have expanded their use of Unfair, Deceptive, or Abusive Acts or Practices (UDAP) statutes, and these laws give attorneys general more immediate powers than federal UDAP:

- Lower standards of proof

- Immediate civil penalties

- Broader definitions of unfair or misleading practices

As a result, practices that technically comply with federal disclosure rules can still trigger state enforcement if the information appears confusing, obscured, or insufficiently prominent.

State-specific fee rules, for example, differ widely and evolve quickly. The examples below illustrate some of these trends:

- Wisconsin limits NSF fees to $15, with prior written notice.

- Maryland caps late fees at 5% and prohibits charging them until a payment is 15 days late.

- Illinois requires a 10-day grace period and written notice before imposing late fees.

- Vermont mandates advance written notice before increasing any fees.

- Oregon requires clear, conspicuous disclosure of late-fee conditions.

- California and New York have taken action on overdraft practices through UDAP scrutiny and proposed fee restrictions.

These diverging regulations require real-time operational differences across states given their different fee caps, grace periods, notice windows, and disclosure standards.

Federal Oversight Is Expanding

The CFPB, FDIC, and OCC have increased focus on TSP involvement in consumer harm, vendor oversight deficiencies and operational reliance. This strengthens the fact that banks are being held accountable for TSP failures and how TPRM is even more critical. Here’s how the federal perimeter is widening:

- The CFPB’s August 2025 proposal for “significant risk of consumer harm” allows direct supervision of nonbanks and third-party service providers (TSPs) including processors, program managers, and fintech partners.

- The Section 1033 Personal Financial Data Rights rule sets new API-driven obligations for data access, data sharing, and consumer control.

- Joint federal–state investigations are increasing, and multi-state settlements are becoming standard.

- Post-outage scrutiny, especially after the 2024 CrowdStrike incident, has elevated federal expectations around operational resilience, recovery times, and dependency on third-party vendors.

The Six Domains Where Rules Are Shifting

These shifts show up most clearly across six core domains where state and federal requirements are evolving in different ways.

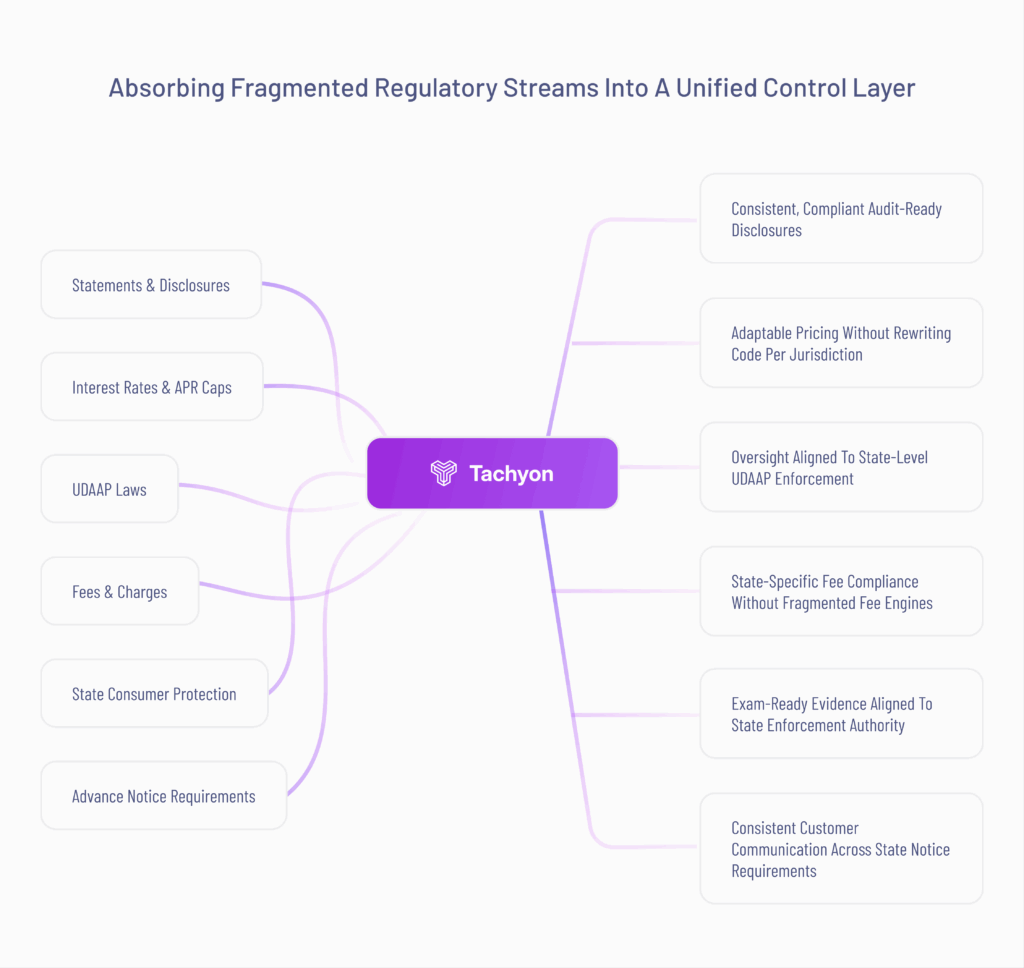

How Tachyon Consolidates Regulatory Complexity

1. Disclosures and Statements

While Reg Z pre-empts state disclosure requirements for national banks, state UDAP laws continue to apply, and state-level pricing rules still bind state-chartered institutions, credit unions, and fintech lenders that do not rely on national-bank rate exportation.

2. Interest Rates and APR/Usury Requirements

State usury laws vary sharply (for example, strict caps in New York and Arkansas, minimal limits in South Dakota and Delaware) creating real complexity for state-regulated banks, credit unions, and fintech lenders that must follow local rules. While national banks rely on interest-rate exportation, others face state efforts to tighten APR limits, require clearer fee and penalty APR disclosures, or apply whichever standard offers stronger consumer protection. And if federal oversight recedes, states may push even stricter pricing rules, even though national banks remain preempted.

3. Fees and Charges

State rules on fees and charges are one of the most active and inconsistent areas of enforcement, with jurisdictions imposing their own caps, grace periods, notice requirements, and disclosure standards. Late-fee limits, NSF caps, and overdraft practices are being reshaped by state-level action, often going beyond federal expectations, and “junk fees” such as balance-transfer or expedited-payment charges are receiving heightened scrutiny when not clearly disclosed.

4. UDAP Consumer Protection Enforcement

State UDAP laws operate independently of federal enforcement and give regulators far broader authority to act quickly on practices they deem unfair or deceptive. Attorneys general can initiate actions directly, some states can define their own prohibited conduct through rulemaking, and most can impose immediate civil penalties—powers that exceed federal UDAP in both scope and speed.

5. Advance Notice Requirements

States are adding more complex advance-notice requirements for fee changes, with varying expectations around timing, clarity, and disclosure. For example, Vermont requires written notice before fee increases, Oregon mandates clear disclosure of fee conditions, and California has strengthened its rules for communicating fee changes. For institutions, this means tracking different notice periods and approval processes across states while keeping customer communications consistent.

6. State Consumer Protection Laws

State consumer-protection authority has expanded significantly, with Section 1042 allowing attorneys general and state regulators to independently enforce major federal laws including the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, Truth in Lending Act, Electronic Funds Transfer Act, and Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act. This has driven more coordinated federal–state investigations, increased data sharing, and a rise in multi-state actions. At the same time, states are widening their regulatory perimeter, adopting tougher penalties, and interpreting consumer-protection statutes more broadly, making state-level enforcement a far more influential force than before.

How Enforcement Is Changing: The New Supervisory Posture

The way regulators enforce and what they expect has changed just as much as the rules themselves.

Heightened Enforcement Intensity

Regulators are taking a firmer line across core compliance areas, especially BSA/AML, where actions rose from about 30 in 2023 to more than 40 in 2024 and penalties exceeded $3 billion. FATF’s updated National Risk Assessment guidance is also pushing institutions to address emerging risks more quickly. The expectation is of faster detection, stronger controls, and proof that programs can keep pace with evolving threats.

Operational and Cyber Resilience Is Now a Priority

Following major outages like the 2024 CrowdStrike incident, resilience has become a top-tier exam focus. Regulators are now focusing on Business Continuity Management, third-party dependency risk, and governed incident logging and reporting. Examiners expect clear RTO/RPOs, auditable failover testing, and evidence that institutions can maintain operations if a critical vendor or TSP is disrupted. Resilience now carries weight comparable to consumer protection.

Third-Party and Fintech Supervision

Under the CFPB’s proposed “significant risk of consumer harm” designation, the Bureau could directly examine nonbanks, fintech partners, processors, and other TSPs. Examiners already test how banks oversee vendor controls and dependencies, holding institutions accountable not only for their own safeguards but for those of the third parties they rely on.

Technology Expectations Are Rising

Regulators are raising expectations around how institutions govern advanced technologies. The CFPB is emphasizing adverse-action explainability, requiring AI- and ML-driven decisions to generate clear, specific reasons for credit outcomes. Bank regulators are reinforcing model-risk expectations through recent supervisory letters, focusing on validated models, documented inventories, and controls for drift. Institutions must show these systems are auditable, transparent, and aligned with supervisory standards.

What Modern Compliance Looks Like

Modern compliance requires platforms to absorb regulatory divergence without fragmentation—capturing state-by-state variation, adapting to federal shifts, and enforcing rules consistently across disclosures, fees, data rights, and operational resilience. As a TSP operating in this environment, Tachyon is built to translate regulatory requirements into governed system behavior rather than manual workarounds.

Tachyon supports this by enabling institutions to:

- Configure jurisdiction-specific rules

- Enforce limits, fee caps, and notice periods programmatically

- Apply rules at authorization, posting, and statement

- Support data-rights and consent flows under §1033

- Segment operational behaviors by state

- Manage communications through configurable templates

- Produce audit-ready evidence on demand

- Detect exceptions and UDAP risk in real time

By centralizing rule logic, applying it deterministically across transaction and communication workflows, and generating evidence as a byproduct of execution, Tachyon operationalizes compliance rather than managing it through patches, releases, or audits.

The Architectural Imperative

What’s emerging across state actions, federal rulemaking, and supervisory expectations is a landscape defined by fragmentation rather than a single, predictable arc. The practical implication is simple: compliance can’t rely on static products, manual patches, or after-the-fact evidence gathering. It requires infrastructure that can capture jurisdictional differences cleanly and enforce them consistently in real time. As divergence becomes the norm, institutions that modernize their architecture will move faster, operate with fewer inconsistencies, and stay ahead of scrutiny.